The rules for adding apostrophes are, by and large, pretty straightforward and consistent, provided you were taught properly in the first place – this is where you, as a Year 2 teacher, come in...

Is there any aspect of punctuation that leaves people more flummoxed than the apostrophe? Reading through social media posts by grown men and women can be enough to make you weep.

It sometimes seems as though the appearance of the letter ‘s’ at the end of a word sends people into panic. Yet it doesn’t have to be this way.

What do Year 2 need to know about apostrophes?

Although apostrophes should be easy enough for adults to handle, they can be a bit tricky for Year 2 children.

For that reason, knowing how to use them is regarded as a greater depth objective at this age. What’s more, they are only expected to be able to use them for singular possession and contraction.

Even so, as the teacher, you first need to be clear in your own mind just what are the rules for apostrophes.

Two basic apostrophe rules for Year 2

There is no need to over-complicate this. There are two basic rules that Year 2 pupils need to know when it comes to apostrophes:

- Possession means belonging. If it belongs to something, it needs an apostrophe before the s: the cat’s toy, the girl’s book, the story’s end.

- Contraction is when words get squashed together and certain letters get removed, as if you didn’t already know. For example, the ‘o’ is removed from the ‘did not’ to make didn’t.

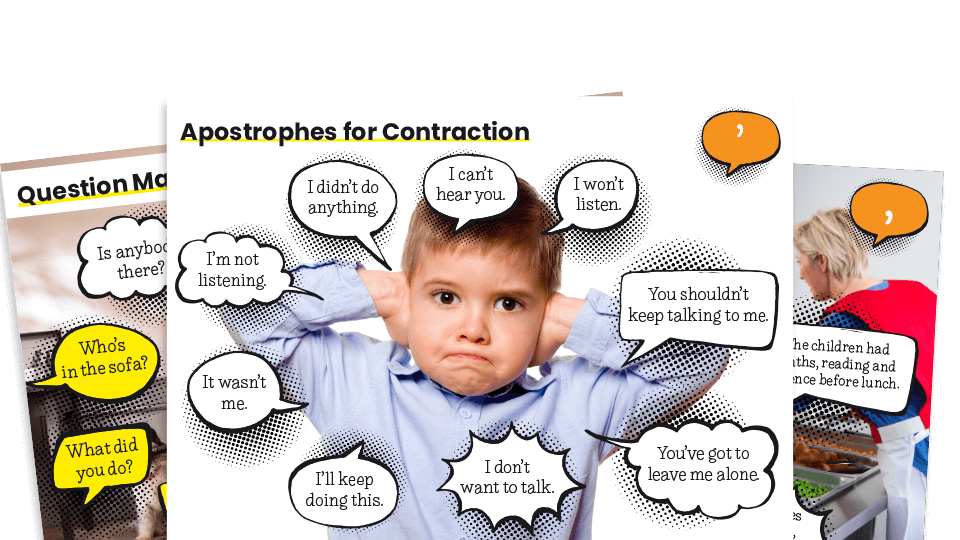

Make apostrophes click with these bright, funny KS1 grammar posters, designed to clearly model apostrophes for possession and contraction through memorable sentences and eye-catching visuals.

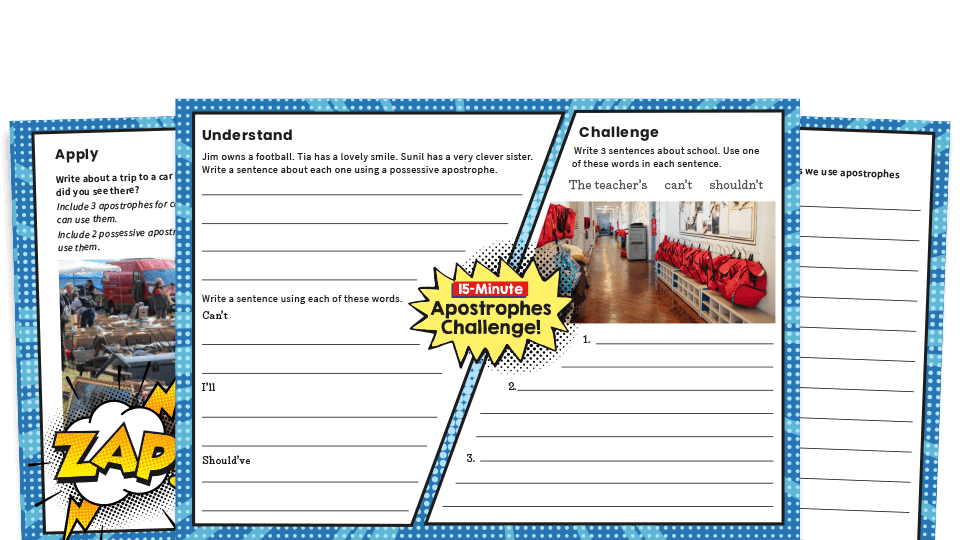

Alternatively, build confidence with apostrophes using this bright Year 2 worksheet, which helps children practise apostrophes for possession and contraction through questions and creative writing tasks.

Contraction resources

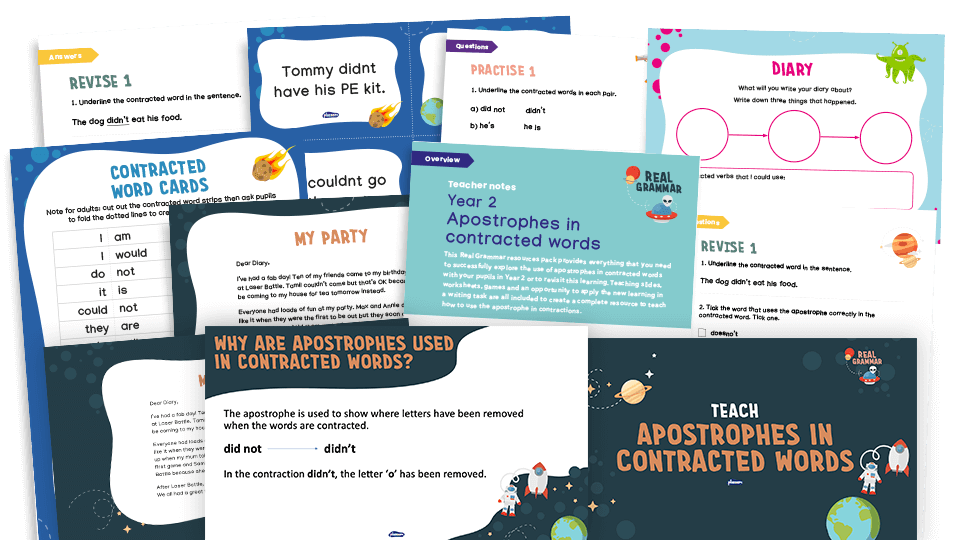

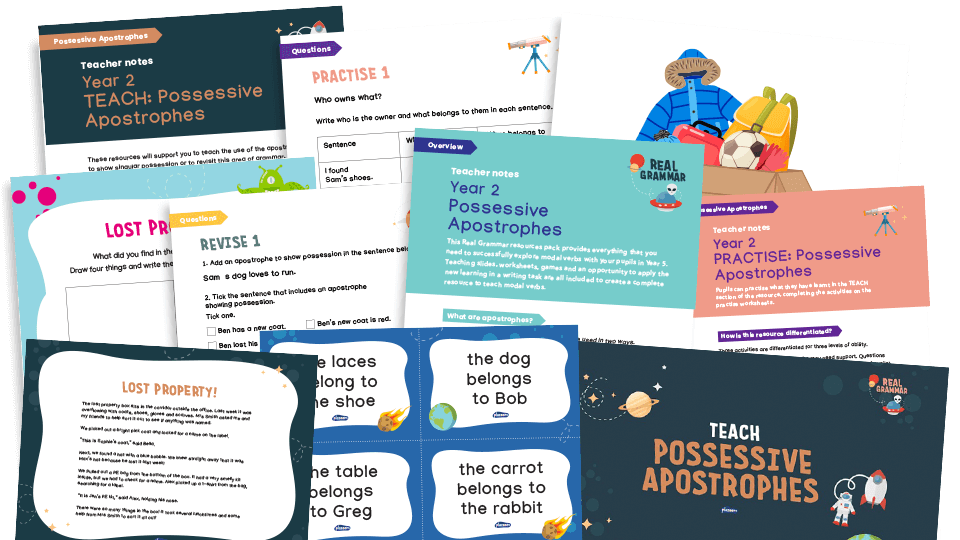

This Year 2 Real Grammar pack breaks learning into clear teach, practise, revisit, apply and revise stages. With slides, games, differentiated worksheets and a writing task, pupils will learn how apostrophes replace missing letters and apply this accurately in their own writing.

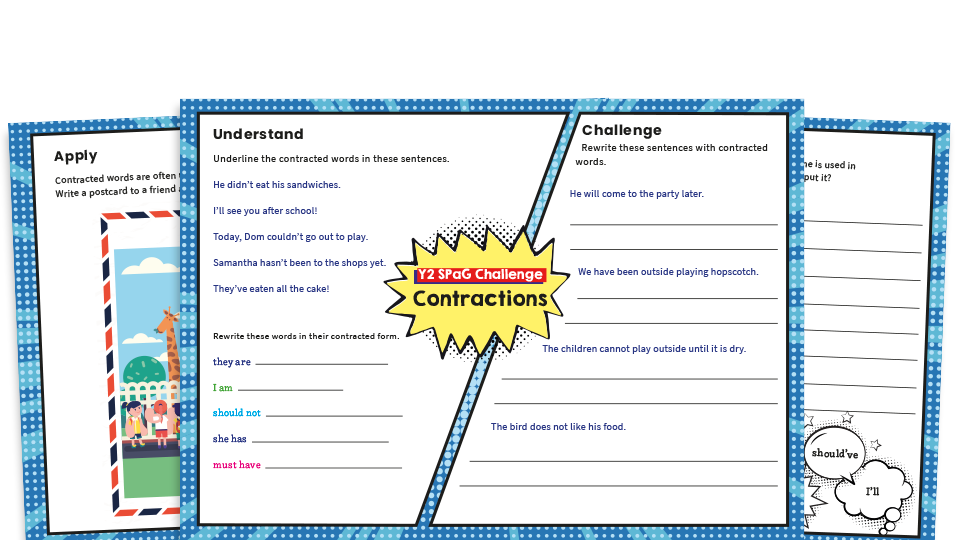

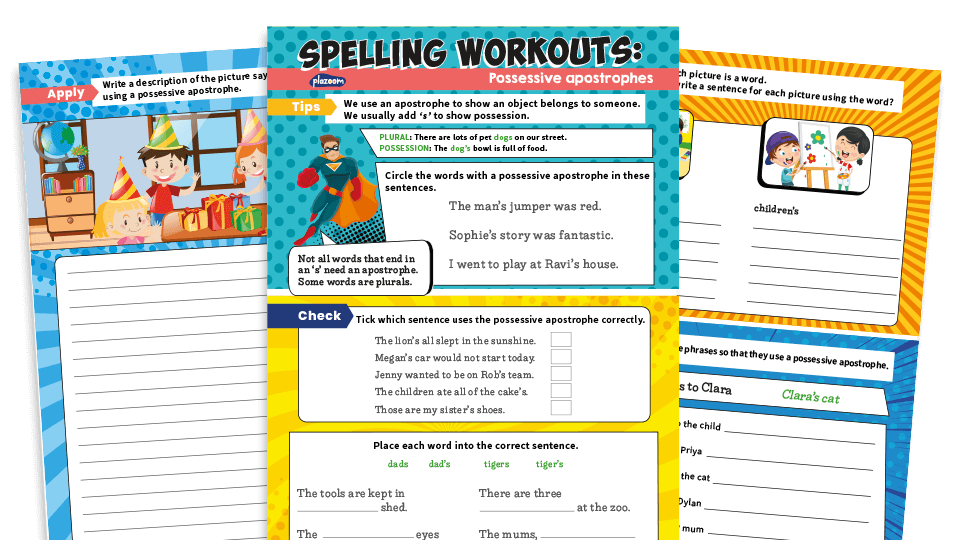

Meanwhile. this bright KS1 worksheet helps Year 2 pupils practise and revise apostrophes in contracted words via five different sections – understand, challenge, test, explain and apply.

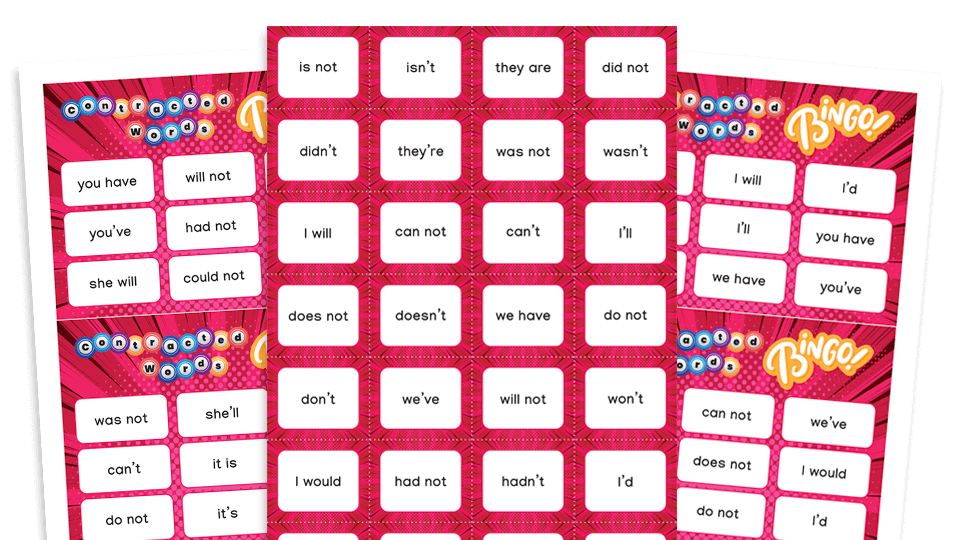

This lively grammar bingo game helps Year 2 pupils revisit apostrophes in contracted words by matching contractions to their full forms and vice versa.

How to make it memorable

Children loves stories. We all do. To help them remember where to put the apostrophe in a contraction, give it a nickname to emphasise where it should go.

For example, you could say that the missing letters have been stolen. So, when modelling writing a contraction, why not say something like, “And there’s your burglar’s calling card” or “Here’s the thief’s footprint,” as you insert the apostrophe where the missing letters would have been.

Apostrophes for possession

Children will intuitively add an ‘s’ to the end of a word to denote possession because they have been hearing it all their lives.

They might not readily connect it with the need for an apostrophe, however, so try to create a memorable narrative to help them.

For example, you could point out that possession is when you have something so you need to have an apostrophe. Give your pupils plenty of opportunities to practise, perhaps using our Year 2 challenge mat for possessive apostrophes.

This Year 2 Real Grammar pack zooms in specifically on using the apostrophe to show singular possession, helping Year 2 pupils clearly understand how an apostrophe shows ownership before moving on to plural possession in later years.

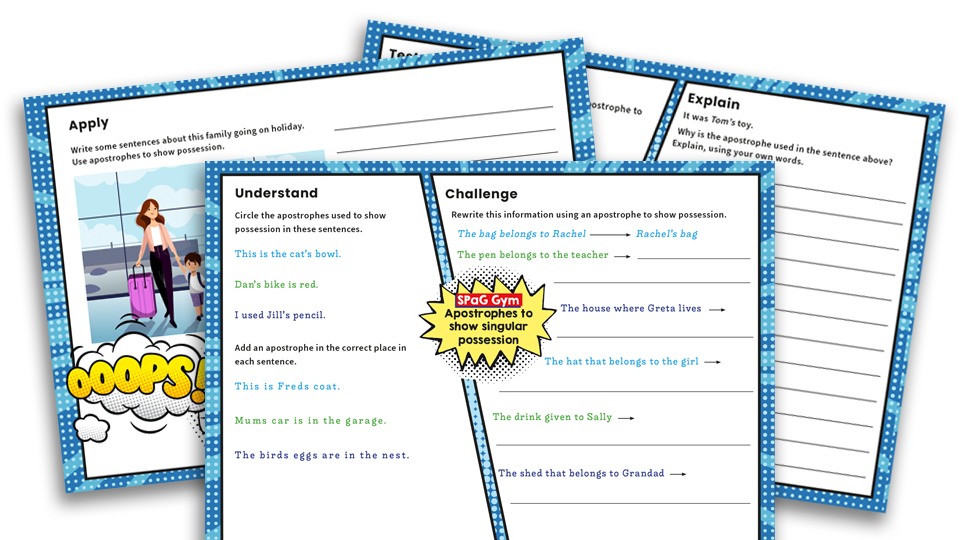

Similarly, this snazzy worksheet helps Year 2 pupils practise and revise singular possessive apostrophes through engaging questions and creative writing tasks.

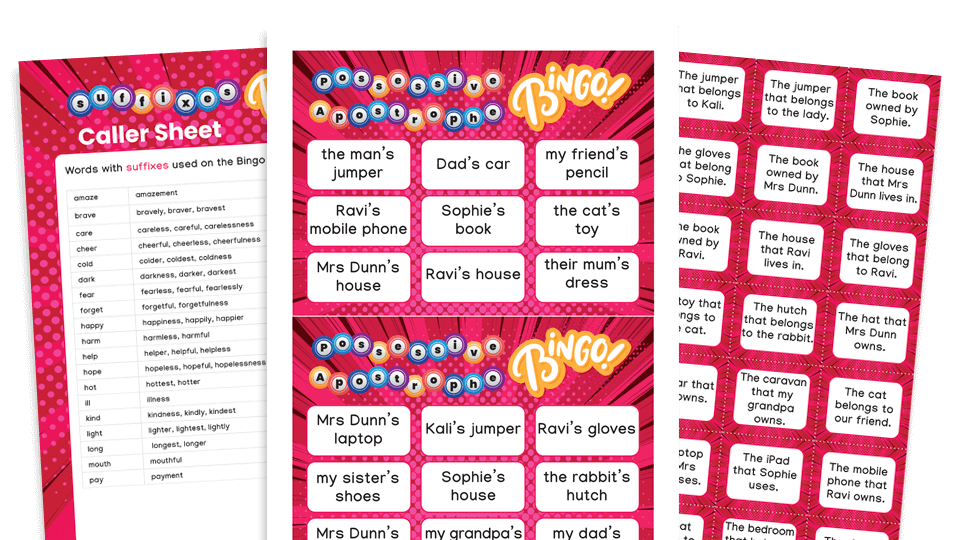

This fun grammar bingo game helps Year 2 pupils revisit singular possessive apostrophes in an engaging, interactive way, giving children plenty of practice spotting and using apostrophes for ownership.

Common mistakes

The grocer's apostrophe

Are you familiar with the grocer’s apostrophe? It became a running joke to highlight the confusion that can be caused by the appearance of an ‘s’ at the end of a word.

There are three main reasons why this might occur:

- verb form (he runs)

- plural (ten green bottles)

- possession (Mum’s car)

Only the last one needs an apostrophe, something fruit stallholders traditionally failed to appreciate when they hand-wrote signs saying things like “Fresh plum’s,” or “Pineapple’s £1 each.”

Its possessive form – the personal pronoun exception

Is there any pair of homophones in the English language that causes more trouble than its/it’s? Consider the sentence 'The tree shed its leaves'.

Logically, you might think that the leaves belong to the tree, so its would need a possessive apostrophe. However, personal pronouns are an exception.

Confusing, yes? Yet somehow this never seems to bother people when they are writing ours, yours or theirs.

Simply pointing this out, even to young children, seems to help when you are teaching its and it’s. Alternatively, just tell them to expand it’s to it is and see whether the sentence still makes sense. If not, the apostrophe is not needed.

Personal names

Apostrophes in names can be a problem. Why does your name have an apostrophe, Ms D’Souza?

Well, once they have learned the rules, why not challenge them to give an explanation – that should help to confirm their understanding.

The apostrophe does not precede an s, so it can’t be a possessive in that sense. Therefore, it must be a contraction. In this case, it comes from the Portuguese words Da Sousa.

The apostrophe in the surname O’Brien has a similar rationale, although it apparently owes more to historical problems that English people had with spelling traditional Irish names!

Possessing singulars that end with 's'

Just because the singular of a word ends with the letter 's' does not change the rules for writing possessives, as in the boss’s desk.

This also holds true with most people’s names: James’s book, Mr Lewis’s classroom. There are a few exceptions, but these are probably too niche to worry about at this age.

Plural possessive

Of course, plurals really put a spanner in the works when it comes to writing possessives. Luckily, as this is a Year 4 objective, you do not have to worry about it at Year 2.

But, if you have successfully taught singular possession and the children have revised it at Year 3, they should have a fairly stable foundation on which to base this new knowledge. There are also our Spelling Workouts for Years 3 and 4 to help.

Now you’re in possession of all the facts, it’s a strong possibility that you’ll be able to teach each apostrophe’s correct usage with confidence. Isn’t that a relief!

Sue Drury qualified as a primary teacher in 1999. Teaching pupils from Year 1 to Year 8, she has held a variety of positions including maths and English subject leader, year leader, and assistant headteacher. Sue has mentored students and NQTs, offering guidance and advice using her years of experience. She created many of Plazoom's literacy resources.